Computational Thinking

Overview

Computational thinking is a flexible model programmers use to formulate a computer-based solution. One of the objectives of the computational thinking model is to get you thinking like a programmer, but also to aid in organizing your approach to problem solving. There are variations of this model, but commonly there are seven identifiable core parts:

- Understand the Problem

- Decomposition

- Data Representation

- Pattern Recognition

- Abstraction

- Algorithm

- Testing

The sequence of this list is based on the most common application of these parts, but by no means is it strict or concrete – depending on the problem, you may omit parts all together or swap some parts around as needed.

Problem solving is often iterative (repeating) and when changes are made in one major part it can have a cascading (snowball) effect on other parts. It is common to have to review other parts or at least anything related to parts that have changed, and this can be difficult to manage so you need to have a process that helps you do this which is where the computational thinking model comes in.

Ultimately what you want to accomplish is the creation of a complete correctly working algorithm that solves the problem which can be used by a programmer to quickly and efficiently code the solution.

Let’s have a closer look at each of these core parts.

Understand the Problem

This may seem obvious, but understanding the problem is critical given the major side effects of what happens when the actual problem is misunderstood. If the problem is not fully understood, the outcome will almost certainly not be a solution to the problem resulting in many angry people (ranging from your peers, stakeholders, and even your family!).

Developing computer solutions is a time demanding and costly process so be sure to have a complete understanding of the problem to avoid wasting time and money on efforts not applicable to the problem you need to solve.

The most common failure is making assumptions. The problem is not always clear and depending on who is responsible for defining the problem (the client versus a project manager for instance), the details can be misleading or completely missing critical information. Assumptions are easy to make in cases where meaning is ambiguous or not explicit so be sure to confirm your assumptions before proceeding.

Here is an example of a poorly worded problem that can lead to all sorts of possible "solutions" because it is too vague and ambiguous:

"The yearly revenue report doesn't work and needs to be corrected before we move on to the next phase of the project."

The issue is in the term "doesn't work". This phrase can so easily be misinterpreted - what exactly doesn't work?

- Are the calculations incorrect?

- Is the data corrupt?

- Could it be a minor cosmetic or formatting problem that only one person doesn't like?

- Is the application interface components not arranged in the way this one person likes?

If you make the assumption of any one of these things, you will most likely be incorrect. In these situations, you MUST seek clarity and precisely determine what "doesn't work" actually means. Without an explicitly defined problem, you can't deliver a solution!

The viewpoint of a "problem" is often very subjective - what one person may see as an issue, another person may not agree. These issues are usually worked out by a project manager but for smaller projects, it is unlikely to have this benefit, so keep your guard up and always make sure there is general consensus supporting a common request.

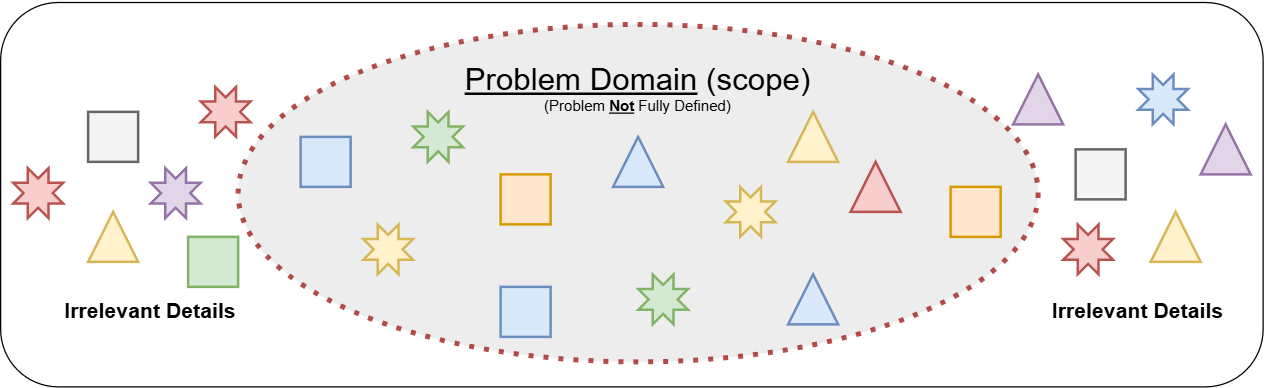

Having a clear understanding of the problem will provide you with the scope and boundaries of both the problem and the solution you need to create. This is extremely important as it will keep you focused on only the pertinent details of the problem and avoid wasting time, money, and effort into unrelated matters.

Decomposition

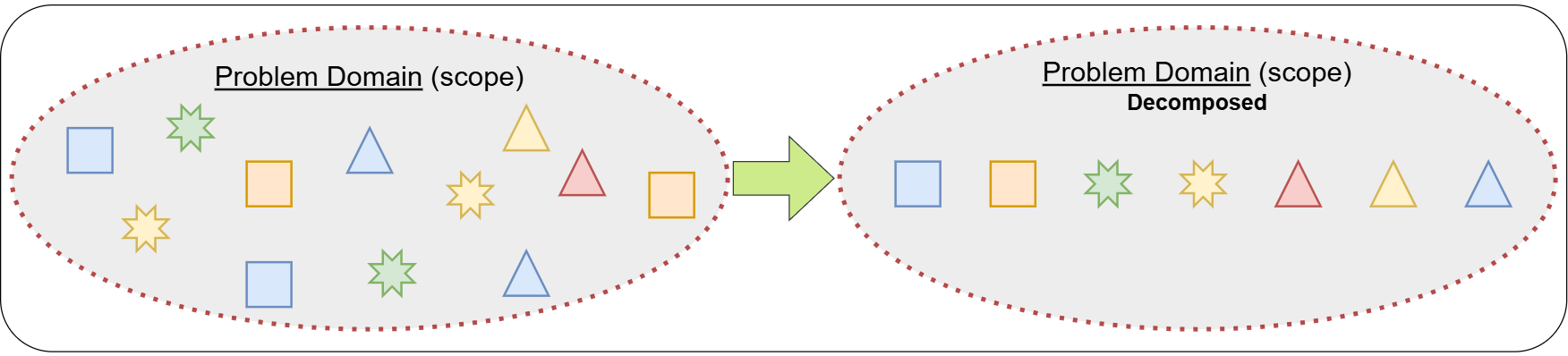

Most problems are too complex or are too dynamic in nature to immediately start creating a solution. Decomposing a problem into many smaller scoped problems greatly simplify many aspects of creating a solution. This step is mainly focused on identifying the major pieces of logic that can be extracted from the problem.

Isolating a specific part of a problem, removes irrelevant parts and greatly reduces the overall complexity for that part. This allows us to easily concentrate only on the important aspects of the smaller problem. Generally, there is no such thing as a complex problem – we just need to break it down into easier to solve smaller parts!

Here is an example of decomposition based on part of a much larger problem :

"The website should provide our administrators the ability to view the clerks who are currently logged-in to the system and for any selected clerk, provide options to send a message, disconnect them from the system, or assign a new task."

There are several significant pieces of the problem we can extract from this:

- The website user-interface (displaying the logged-in clerks and providing action options when a specific clerk is selected).

- Possible function name: "InitializeClerksLoggedIn"

- This function's scope will be limited to focusing only on preparing the interface, getting and displaying the logged-in user data listing, and providing the options for a selection.

- Sending a message to a specific clerk

- Possible function name: "SendClerkMessage"

- This function's scope will be limited to focusing only on how an administrator can send a message to a selected clerk from the list.

- Disconnecting a specific clerk

- Possible function name: "DisconnectClerk"

- This function's scope will be limited to focusing only on how a selected logged-in user is disconnected.

- Assigning a new task to a specific clerk

- Possible function name: "AssignClerkTask"

- This function's scope will be limited to focusing only on how a selected logged-in user is assigned a new task.

These are four major pieces of the problem that can be extracted and focused on to solve individually. These can be compartmentalized into specific functions where the logic can be isolated to solve only that specific part of the problem.

The process of identifying smaller parts of the problem can validate your understanding of the problem and confirms the overall scope. Often this process will identify missed or undefined parts of the problem that will need to be clarified which could likely expand the scope or sometimes have the opposite effect where irrelevant parts are identified and could likely reduce the scope.

Reducing a large problem into many smaller parts, promotes a lot of flexibility in how you will orchestrate and reassemble these smaller solutions together when finalizing a complete solution. It is important to take your time in this phase to filter for only the critical information and processes.

- This stage often identifies the potential core

functions(procedures) to be created and used in the solution. - Functions represent algorithms comprised of several logical steps which perform a specific task (this will be described in more detail later on)

Data Representation

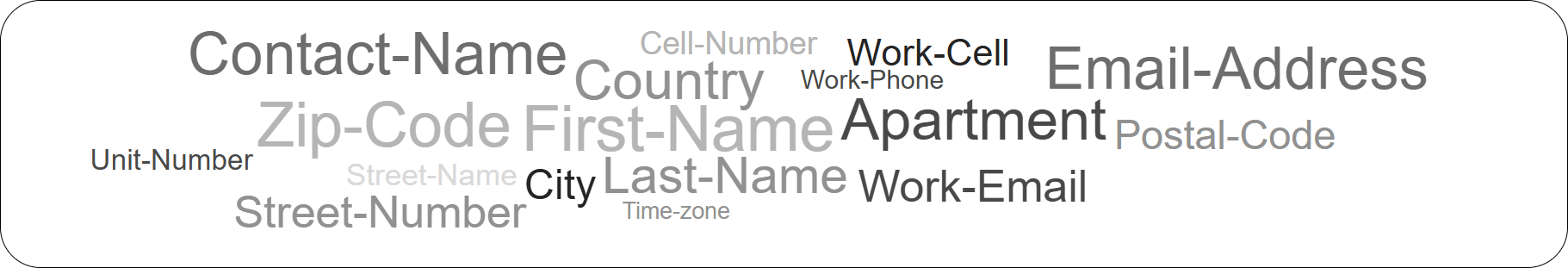

Information (data) is a major part of a computer-based solution since the data can significantly impact how the solution works and what it must do with the data. How data is received, used, or output is not the focus in this step, rather the objective is to identify WHAT the relevant data is and to ensure it is represented in a way it can be used in the solution.

Data representation is accomplished by representing data with variables (the technical aspect of this is covered later). Variables are named placeholders which can be referred to within the solution to access specific information by name to refer to the value. For example, if we needed to manage data about a person’s contact information, some key data would be:

| Information | Variable | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Full Name | name | Jiminy Cricket |

| Email Address | email | jcricket@domain.com |

| Cell Number | cell | (123) 123-1234 |

The important information in this example is a person’s name, email address, and cell phone number. These important pieces of data are mapped or represented by variables which can be named to anything you wish but should almost always apply a self-documented identifier to clearly represent the data while not being too long.

When we refer to the variable name, it will represent a value corresponding to that variable which in this example is Jiminy Cricket. Likewise, if we needed to refer to the email address data jcricket@domain.com, then the variable email would be used to target this information.

One question you may raise during this phase is about how much data you need to manage/represent and how granular (broken down into parts) you need to make it. In the preceding example, there is a name variable which includes the full name – does the solution require you to make a distinction between first and last name parts? If so, then you will need to represent this data separately where the name variable would need to be split into two variables such as firstName and lastName (or surname). Eliminating the original variable name. When you need to refer to the full name, you would simply join these two variables accordingly.

There is an additional more advanced concept we can use to help manage more complex data representation, but this will be discussed later in two other sections:

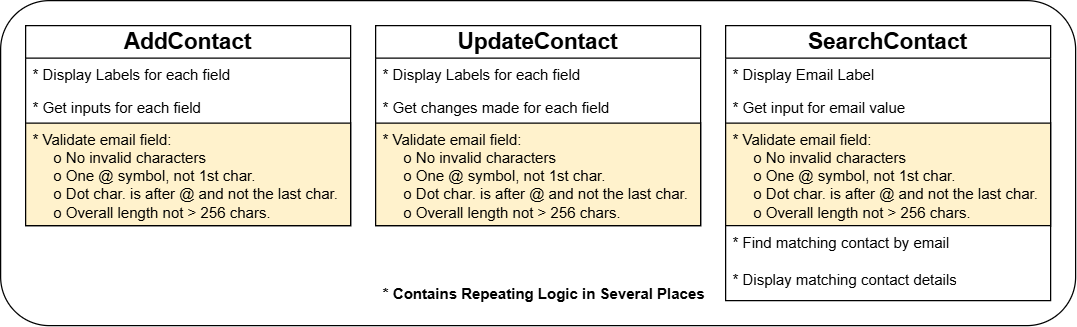

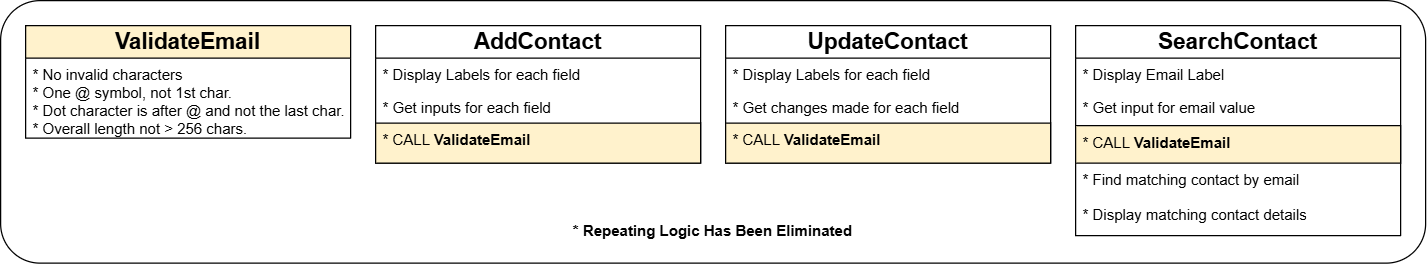

Pattern Recognition

After decomposing a problem into several smaller parts (let’s say for example we have identified three functions as illustrated in the above image) and in outlining each of those functions, you notice repetition in the logic. The repetition can be within the same function and/or in other functions – this is undesirable! Why? Let’s analyze the example further.

The breakdown of these functions as described below is an overview only. You will learn how to properly document logic later.

Function:

AddContact

- This will detail all the steps needed to add the details of a new contact

- After the user enters an email address, the email field will be validated to ensure the email entered matches the expected format (

value@value.value).

- The email validation logic will require several steps of logic to implement:

- Makes sure there are no invalid characters

- Makes sure there is a single

@symbol and not the first character- Makes sure there is a

.symbol and at least 2 characters after the@and not the last character- Makes sure the overall length is not excessive (ie. > 256 characters)

Function:

UpdateContact

- This will detail all the steps needed to update the details of an existing contact

- After the user enters an email address, the email field will be validated to ensure the email entered matches the expected format (

value@value.value).

- The email validation logic will require several steps of logic to implement:

- Makes sure there are no invalid characters

- Makes sure there is a single

@symbol and not the first character- Makes sure there is a

.symbol and at least 2 characters after the@and not the last character- Makes sure the overall length is not excessive (ie. > 256 characters)

Function:

SearchContact(based on email field)

- This will detail all the steps needed to search for a specific contact based on a user-entered email address and then display the contact details

- After the user enters an email address, the email field will be validated to ensure the email entered matches the expected format (

value@value.value).

- The email validation logic will require several steps of logic to implement:

- Makes sure there are no invalid characters

- Makes sure there is a single

@symbol and not the first character- Makes sure there is a

.symbol and at least 2 characters after the@and not the last character- Makes sure the overall length is not excessive (ie. > 256 characters)

All three functions contain the same email validation logic which means this would be coded (by a programmer) three separate times! Why is this undesirable?

What if the email validation logic has a bug (an error that doesn’t properly validate the email)? You would have to review and change potentially all three functions that repeat this logic. It is very inefficient to maintain this type of design and is error-prone given the redundancy (could have three versions of validation all of which could be slightly different). Another case is if the email formatting rules change, again, this would require updating all occurrences of this logic. What is the solution to this?

You should extract the repeating logic into its own function where the logic can be defined once, then in other parts of the solution where you need that logic implemented, you execute that logic when and where you need it. The function you create should be given a meaningful name that best describes what it does so it’s easy to use and communicate. In this example the function could be called ValidateEmail. Now, the three other functions can be updated to CALL the new function ValidateEmail eliminating the redundancy of fully detailing how that logic works in three different places!

*NEW* Function:

ValidateEmail

- Validates the email address to ensure the email entered matches the expected format (

value@value.value) snf will be the ONLY place where this logic is defined.- Makes sure there are no invalid characters

- Makes sure there is a single

@symbol and not the first character- Makes sure there is a

.symbol and at least 2 characters after the@and not the last character- Makes sure the overall length is not excessive (ie. > 256 characters)

- Now this logic can easily be used by other parts of the solution whenever needed without repetition.

Function:

AddContact

- This will detail all the steps needed to add the details of a new contact

- After the user enters an email address, CALL

ValidateEmail

Function:

UpdateContact

- This will detail all the steps needed to update the details of an existing contact

- After the user enters an email address, CALL

ValidateEmail

Function:

SearchContact(based on email field)

- This will detail all the steps needed to search for a specific contact based on a user-entered email address and then display the contact details

- After the user enters an email address, CALL

ValidateEmail

Several lines of logic are now removed from each of the functions (AddContact, UpdateContact, and SearchContact) because there is now a common function called ValidateEmail and each function that needs this logic implementation simply CALL's that function (ex: CALL ValidateEmail) when needed.

The below image illustrates the correction to the illustration at the beginning of this section.

There is another situation where you may reveal a repeating pattern but does not necessarily require a function to address it. Sometimes the repetition is purely semantic (logical) and can be handled using iteration which is a concept covered later.

Patterns exhibiting a duplication in logic can usually be addressed by making a dedicated function which contains the logic in a single place. The function can then be called from anywhere in the solution to implement that logic whenever needed. Functions provide many benefits:

- Single place to manage the logic

- Simplifies the reading of logic (don't need to know how the logic works everywhere it is used)

- Reduces the overall footprint size of the solution by eliminating redundant detailed logic

There are also situations where logic duplication is purely semantic (logical) and can be managed using a logic control method referred to as iteration.

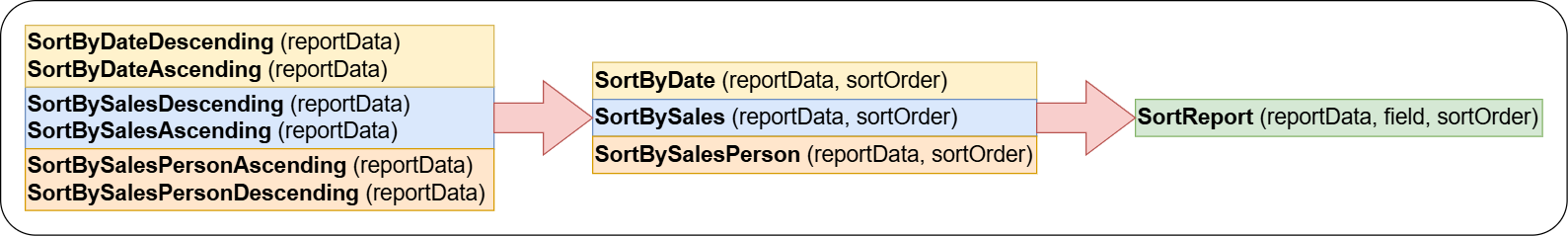

Abstraction

Abstraction is an extension of pattern recognition in that you can observe similar logic across many parts of the solution but are different in only minor ways, however the main essence of the logic is the same. Logic where the overall concept or idea can be reused but execute slightly differently across different contexts is an abstraction. Let's look at an example of this.

An application is needed to produce a business report for management that shows weekly data about their sales. The report data contains the date (formatted as: YYYY-MM-DD and is the Sunday of each week), salesperson name, and the total sales for that salesperson for that week - all reports use the same data but there are six main ways to view the report:

- By the date -> ascending order

- By the date -> descending order

- By the salesperson's total sales -> ascending order

- By the salesperson's total sales -> descending order

- By the salesperson's name -> ascending order

- By the salesperson's name -> descending order

Since all the report views use the same report data, we will represent the dataset with a variable reportData.

You might initially break this down so there is a function for each possible report view (notice the report data is sent to the function so the function can access the data):

SortByDateDescending(RECEIVES: reportData)SortByDateAscending(RECEIVES: reportData)SortBySalesDescending(RECEIVES: reportData)SortBySalesAscending(RECEIVES: reportData)SortBySalesPersonAscending(RECEIVES: reportData)SortBySalesPersonDescending(RECEIVES: reportData)

If we want to view the report by date in ascending order, then we would have to call the appropriate function:

CALL SortByDateAscending(reportData)

Each report view would have it's own specific function. This works fine, but you could further refine this by applying abstraction to reduce these 6 functions down to 3 functions. How? Each main report has two variants: sorting by ascending or descending order. We can take the concept of sorting by ascending or descending and merge this logic into one function for each main report view.

SortByDate(RECEIVES: reportData)SortBySales(RECEIVES: reportData)SortBySalesPerson(RECEIVES: reportData)

But wait - how can we use these functions to get the desired sorting order? Simple! We would send an additional variable or value to the respective function that would instruct the function the desired sort order. Let's update the functions now to include the extra information:

SortByDate(RECEIVES: reportData, sortOrder)SortBySales(RECEIVES: reportData, sortOrder)SortBySalesPerson(RECEIVES: reportData, sortOrder)

Now, when we call a report function we can send both the reportData AND include another piece of information that specifies the desired sortOrder. The function will use the sortOrder variable to determine the desired sorting order. Let's try it again now with this new abstracted function for the SortByDate:

CALL SortByDate(reportData, "ASCENDING")

When we call the function providing the "ASCENDING" value, it is assigned to the variable sortOrder which the function will use to evaluate what order to sort the report.

Are we done yet? Could this be abstracted even further? YES! The primary concept being implemented in these functions is to sort data by a specific field (attribute) of data. We can apply the same idea as we did for the sortOrder and add another piece of information to send the function which would specify the field or attribute of the data to sort on! If we added this extra piece of information, we can now reduce these three functions down to ONE! Here's what it would look like:

SortReport (RECEIVES: reportData, field, sortOrder)

With this function, it can be called in many different ways but no matter what, it will sort the data based on the field we want and in the ascending or descending order using the conditions we send to the function that are captured in the variables: field and sortOrder. If we want the report to be sorted by salesperson in descending order, we can call the function like this:

CALL SortReport(reportData, "salesperson", "DESCENDING")

Abstraction is the process of simplifying something back to a general concept or idea.

Sometimes abstraction can be over-applied (just because you can abstract something doesn't necessarily mean you should). There are varying scales at which you should apply it and is always evaluated on a case-by-case basis. If the abstraction creates too much additional complexity then you should reevaluate and find another approach.

In the above example, where the second level of abstraction was applied where we reduced three functions down to one function, might have taken it too far as that function is now a lot more complex. Perhaps leaving it at the first level of abstraction having three functions would be more suitable and manageable to maintain (but is certainly better than the original six functions!).

Algorithm

An algorithm is ultimately what we are trying to accomplish. An algorithm is a complete set of instructions in the sequence they must occur to solve a problem. Algorithms describe in detail how the logic works step-by-step. This is what would be provided to a programmer to code a solution.

The scope of an algorithm can be small or vast depending on the problem it is addressing. When we decompose larger problems into smaller ones, each smaller one (ex: function) has its own algorithm, but when we design the 'main' function that orchestrates the overall solution, it will tie together other algorithms (functions) as required to provide a full set of instructions for the entire solution.

Since algorithms detail a solution, they must be tested to ensure it in-fact provides a working solution to the entire problem and stays within the scope of the problem (see next sub-section on Testing).

To manage and communicate algorithms, programmers primarily use pseudocode as it is more efficient to work with and can provide more detail. However, flowcharts are used to provide a higher level view of the solution and is generally less detailed due to the complexity of the layout using graphical symbols. These forms of communicating logic will be covered in the next major section (Documenting Logic).

Testing

Testing should be done repeatedly throughout all parts of the computational thinking model. The scale at which you test will depend on what it is you need to test. Making changes to established logic for instance would be one such time to do a concentrated and focused test to ensure the changes didn't break anything or cause other unforeseen side-effects.

The more targeted and frequent your testing is, the better your solution will be. However in reality, we usually do not have enough time to do extensive detailed testing, so we must be efficient about how and what we test (something you get better at in time).

What we minimally should test are all the known major logic flows that must occur to solve the problem and as the application would be used by users the majority of the time. We accomplish this by creating "use-cases". These are the expected and common scenario's that would occur in the execution of the solution. Prioritizing the features and critical logic parts of the solution that are used the most by users will validate and ensure the solution is mostly bug-free and confirms it actually solves the problem.

Testing is where we often reveal weaknesses in the logic and where applications mostly fail, is in the unexpected things! After the core logic of the solution is tested, you would move on to more robust testing and include out of the norm conditions. One way to target this is the ask "what if.." and run that scenario through your solution to see if it works as expected. Be warned, once you start looking for exceptions and asking "what if", this can take you well beyond what is "reasonable" to test so know when to stop and when you have reached the "obscure" that goes well-beyond normal exceptions.

Summary

In summary, programmers should plan a solution applying the computational thinking model BEFORE starting any coding. Planning ahead and having a framework to work from accelerates your coding time and results in substantially fewer errors since the difficult part of determining the logic and flow of the solution is already done. As a programmer, the coding part should only involve the syntax and implementation of the logic based on a prepared plan.

The extent to which you apply the computational model will vary depending on the problem. All parts of the model are important and will lead to great improvements in your skills to build solutions, however a couple of the parts are mandatory and you should definitely get in the habit of doing the following ALWAYS:

- Understand the problem

- Decomposition

The other parts may take time and repetition in applying the concepts before you get comfortable and more skilled at using them. Abstraction is probably the most challenging of them because often it can be over-applied (just because you can abstract something doesn't necessarily mean you should, and there are varying scales at which you can apply it).

The act of coding a solution into a program should actually be the least time consuming part of a project. If you find otherwise, it likely means you aren't working from a planned solution, or the prepared logical plan is poorly done and needs more work.

It is always worth the time to fix the plan than it is to waste significant time debugging and rearranging your code after it's been coded!